“As psychoanalyst Erik Erikson once noted, there are only two choices: Integration and acceptance of our whole life-story, or despair.”

From Ruthless Trust by Brennan Manning

“As psychoanalyst Erik Erikson once noted, there are only two choices: Integration and acceptance of our whole life-story, or despair.”

From Ruthless Trust by Brennan Manning

Over Christmas I neglected my plants, and I thought my rosebush had died. I kept watering it, though, and the dead leaves fell off and new ones began to grow. This afternoon I noticed a single rose starting to bloom. The tiny red bud commands attention among the green of the rose leaves, bamboo and geranium in the window, and against the white of the wall. It’s a sign of hope! Rebirth, new life, right here in my bedroom.

This did not go at all as planned, if I ever had a plan. It had something to do with impressing everybody, but doing it without appearing to, effortlessly, the way I tell jokes,without smiling, looking away afterwards, leaving people to laugh or not, too cool to acknowledge my own cleverness.

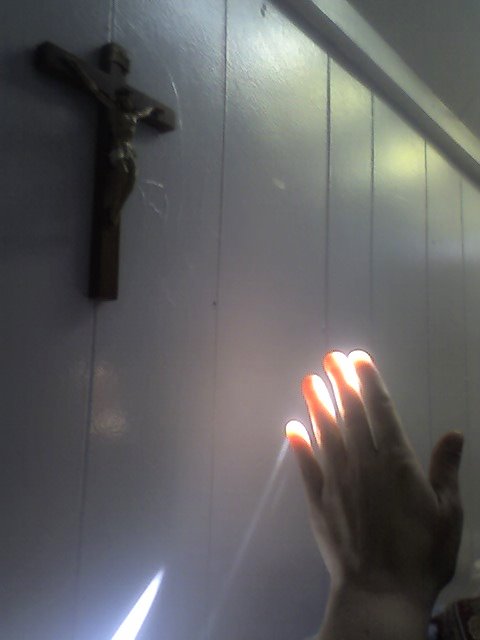

But I was broken out of my intellect, my intention, my talent by the brokenness of my body, and though I wanted to relate to Christ in his witty reparte, his compassion, his healing, I now relate most to his twisted form on the cross, eyes shut in pain, not yet dead, not yet ressurrected, not yet ascended. My Lord, the suffering, naked, four inch plastic form on the eight inch wooden cross.

I am not making a theology out of this. Far be it from me. I am telling you what I do not know, not what I know. I am in pain all the time. I am dizzy, nauseaus, exhausted, and this is before the side effects from the medications kick in.

Jesus’ features are not twisted in agony. If you didn’t know better you might almost think he looked peaceful. But I think that I recognize the movement inward that a long-suffering spirit makes. It is close to meditation. You have less to do with the world, with what is going on around you. Physical and emotional sensation takes over and then, somehow, you sink below that, to a place deeper than that.

The contemplatives teach that at our very center the Spirit is constantly praying; that our act of prayer consists of joining in awareness with that ongoing prayer. This is the only kind of prayer I can hope for, now.

I place a finger on each nail and press the wooden cross to my heart, the broken body of Christ against my own.

If you came this way,

Taking the route you would be likely to take

From the place you would be likely to come from,

If you came this way in may time, you would find the hedges

White again, in May, with voluptuary sweetness.

It would be the same at the end of the journey,

If you came at night like a broken king,

If you came by day not knowing what you came for,

It would be the same, when you leave the rough road

And turn behind the pig-sty to the dull facade

And the tombstone. And what you thought you came for

Is only a shell, a husk of meaning

From which the purpose breaks only when it is fulfilled

If at all. Either you had no purpose

Or the purpose is beyond the end you figured

And is altered in fulfilment. There are other places

Which also are the world’s end, some at the sea jaws,

Or over a dark lake, in a desert or a city—

But this is the nearest, in place and time,

Now and in England.

If you came this way,

Taking any route, starting from anywhere,

At any time or at any season,

It would always be the same: you would have to put off

Sense and notion. You are not here to verify,

Instruct yourself, or inform curiosity

Or carry report. You are here to kneel.

This is an exerpt from Eliot’s The Four Quartets, and it is a vivid description of the experience I have been having this past year, which I can also find described in books like The Dark Night of the Soul by Saint John of the Cross.

The Latin for “dark” is obsura — obscure. We don’t understand why the removal of our joy, our peace, our dearly loved connection with our Lord is necessary, but we trust that it is. We have prayed to give Him everything, and it turns out that the taking away of everything includes the things we depended on for our faith. These things are not He. As a character in a Charles Williams novel says, “Neither is this Thou.”

We wanted to live for Him. We find we can barely live at all. We wanted to conquer the world for His Kingdom. We find we can not even conquer ourselves.

Even this is too much explanation. It is obscure. I am not here to instruct myself, nor to carry report. I am here to kneel.

*Thanks to Sleight of Hand for sending me to this passage.

“But all the wickedness in the world which man may do or think is no more to the mercy of God than a live coal dropped in the sea.”

–William Langland

Life is never a straight line. Even when you know where you want to go, you often find yourself off course. This is not the time to panic. It is also not a time to swing the wheel at random, hoping to fall into line with another traveler, or to be caught in a current. Movement seems reassuring, but we must make sure we are moving in the right direction. Sometimes stillness is the thing.

So with rest. God met Elijah in his rest, and ministered to him there, “Get up and eat, for the journey is too much for you.” If the Spirit of God is calling us to rest, it is no good to work all day and night, even — perhaps especially — in God’s service and in his Name. God is patiently waiting for us in our beds, where we are prone and unmoving, our posture as helpless and as trusting as a baby’s. There are sermons to be written and preached, there are people who haven’t heard the gospel, there are hungry people who need to be fed, and lonely people who need to be noticed, but if God has said to us, “rest” we will not find him in the sermon, in the witnessing, in the hungry and the lonely. He is in our own bed, where he told us to meet him, if we would only listen.